Making and transporting hay

Hay production and harvest, colloquially known as "making hay", "haymaking", or "doing hay", involves a multiple step process: cutting , drying or "curing", processing, and storing. Hay fields do not have to be reseeded each year in the way that grain crops are, but regular fertilizing is usually desirable and over-seeding a field every few years helps increase yield.

Methods and the terminology to describe the steps of making hay have varied greatly throughout history, and many regional variations still exist today. However, whether done by hand or by modern mechanized equipment, tall grass and legumes at the proper stage of maturity must be cut, then allowed to dry (preferably by the sun), then raked into long, narrow piles known as windrows. next, the cured hay is gathered up in some form (usually by some type of baling process) and placed for storage into a haystack or into a barn or shed to protect it from moisture and rot.

During the growing season, which is spring and early summer in temperate climates, grass grows at a fast pace. It is at its greatest nutritive value when all leaves are fully developed and seed or flower heads are just a bit short of full maturity. When growth is at a maximum in the pasture, if judge correctly, the pasture is cut. Hay cut too early will not cure as easily due to high moisture content, plus it will produce a lower yield per acre than longer, more mature grass. But hay cut too late is coarser, lower in resale value and has lost some of its nutrients. There is usually about a two-week "window" of time in which hay is at its ideal stage for harvesting.

Hay can be raked into rows as it is cut, then turned periodically to dry, particularly if a modern swather is used. Or, especially with older equipment or methods, the hay is cut and allowed to lie spread out in the field until it is dry, then raked into rows for processing into bales afterwards. During the drying period, which can take several days, the process is usually speeded up by turning the cut hay over with a hay rake or spreading it out with a tedder. If it rains while the hay is drying, turning the windrow can also allow it to dry faster. However, turning the hay too often or too roughly can also cause drying leaf matter to fall off, reducing the nutrients available to animals. Drying can also be speeded up by mechanized processes, such as use of a hay conditioner, or by use of chemicals sprayed onto the hay to speed evaporation of moisture, through these are more expensive techniques, not in general use except in areas where there is a combination of modern technology, high prices for hay and too much rain for hay to dry properly.

Once hay is cut, dried and raked into windrows, it is usually gathered into bales or bundles, then hauled to a central location for storage. In some places, depending on geography, region, climate, and culture, hay is gathered loose and stacked without being baled first.

Hay must be fully dried with baled and kept dry in storage. If hay is baled while too moist or becomes wet while in storage, there is a significant risk of spontaneous combustion. Hay stored outside must be stacked in such a way that moisture contact is minimal. Some stacks are arranged in such a manner that the hay itself "sheds" water when it falls. Other methods of stacking use the first layers or bales of hay as a cover to protect the rest. To completely keep out moisture, outside haystacks can also be covered by tarps, and many round bales are partially wrapped in plastic as part of the baling process. Hay is also stored under a roof when resources permit. It is frequently placed inside sheds, or stacked inside of a barn. On the other hand, care must also be taken that hay is never exposed to any possible source of heat or flame, as dry hay and the dust it produces are highly flammable.

Early Methods

Early farmers noticed that growing fields produced more fodder in the spring than the animals could consume, and that cutting the grass in the summer, allowing it to dry and storing it for the winter provided their domesticated animals with better quality nutrition than simply allowing them to dig through snow in the winter to find dried grass. Therefore, some fields were "shut up" for hay.

Up to the end of the 19th century, grass and legumes were not often grown together because crops were rotated. By the 20th century, however, good forage management techniques demonstrated that highly productive pastures were a mix of grasses and legumes, so compromises were made when it was time to mow. Later still, some farmers grew crops, like straight alfalfa, for special-purpose hay such as that fed to dairy cattle.

Much hay was originally cut by scythe by teams of workers, dried in the field and gathered loose on wagons. Later, haying would be done by horse-drawn implements such as mowers. With the invention of agricultural machinery such as the tractor and the baler, most hay production became mechanized by the 1930s.

After hay was cut and had dried, the hay was raked or rowed up by raking it into a linear heap by hand or with a horse-drawn implement. Turing hay, when needed, originally was done by hand with a fork or rake. Once the dried hay was rowed up, pitch forks were used to pile it loose, originally onto a horse-drawn cart or wagon, later onto a truck or tractor-drawn trailer, for which a sweep could be used instead of pitch forks.

Loose hay was taken to an area designated for storage -usually a slightly raised area for drainage - and built into a hay stack. The stack was made waterproof as it was built ( a task of considerable skill) and the hay would compress under its own weight and cure by the release of heat from the residual moisture in the hay and from the compression forces. The stack was fenced from the rest of the paddock in a rick yard, and often thatched or sheeted to keep it dry. When needed slices of hay would be cut using a hay-knife and fed out to animals each day.

On some farms the loose hay was stored in a shed or barn, normally in such a way that it would compress down and cure. Hay could be stored in a specially designed barn with little internal structure to allow more room for the hay. Alternatively an upper storey of a cow-shed or stable was used, with hatches in the floor to allow hay to be thrown down into hay-racks below.

Depending on region, the term "hay rick" could refer to the machine for cutting hay, the hay stack or the wagon used to collect the hay.

Modern mechanised techniques

Modern mechanized hay production today is usually performed by a number of machines. While small operations use a tractor to pull various implements for mowing and raking, larger operations use specialized machines such as a mower or a swather, which are designed to cut the hay and arrange it into a windrow in one step. Balers are usually pulled by a tractor, with larger balers requiring more powerful tractors.

Mobile balers, machines which gather and bale hay in one process, were first developed around 1940. The first balers produced rectangular bales small enough for a person to lift, usually between 70 and 100 pounds each. The size and shape made it possible for people to pick bales up, stack them on a vehicle for transport to a storage area, then build a haystack by hand. However, to save labor and increase safety, loaders and stackers were also developed to mechanise the transport of small bales from the field to the haystack. Later, bales were developed capable of producing large bales that weigh up to 3000 pounds.

Small bales

Small bales are still produced today. While balers for small bales are still manufactured, as well as loaders and stackers, there are some farms that still use equipment manufactured over 50 years ago, kept in good repair. The small bale remains part of overall ranch lore and tradition with "hay bucking" competitions still held for fun at many rodeos and county fairs.

Small bales are stacked in a criss-crossed fashion sometimes called a "rick" or "hayrick". Since rain washes nutrition out of the hay and can cause spoilage or mold, hay in small bales is often stored in a hayshed or protected by tarpaulins. If this is not done, the top two layers of the stack are often lost to rot and mold, and if the stack is not arranged in a proper hayrick, moisture can seep even deeper into the stack.

People who own small numbers of livestock, particularly horses, still prefer small bales that can be handled by one person without machinery. There is also a risk that hay baled while still too damp can produce mold inside the bale, or decaying carcasses of small creatures that were accidentally killed by baling equipment and swept up into the bales can produce toxins such as botulism. Both can be deadly to nonruminant herbivores, such as horses, and when this occurs, the entire contaminated bale should be thrown out, another reason some livestock owners continue to support the market for small bales.

When possible, hay, especially small square bales like these, should be stored under cover and protected from the elements.

Large bales

Many farmers, particularly those who feed large herds, have moved to balers which produce much larger bales, maximizing the amount of hay which is protected from the elements. Large bales come in two types, round and square. "Large Square" b ales, which can weigh up to 1000 kg (2,200 lb), can be stacked and are easier to transport on trucks. Round bales, which typically weigh 300-400 kg (700-900 lb), are more moisture resistant, and pack the hay more densely (especially at the center). Round bales are quickly fed with the use of mechanized equipment.

The ratio of volume to surface area makes it possible for many dry-area farmers to leave large bales outside until they are consumed. Wet-area farmers and those in climates with heavy snowfall either stack round bales under a shed or tarp, but have also developed a light but durable plastic wrap that partially encloses bales left outside. The wrap repels moisture, but leaves the ends of the bale exposed so that the hay itself can "breathe" and does not begin to ferment. However, when possible to store round bales under a shed, they last longer and less hay is lost to rot and moisture.

Round bales are harder to handle than square bales but compress the hay more tightly. This round bale is partially covered with net wrap, which is an alternative to twine.

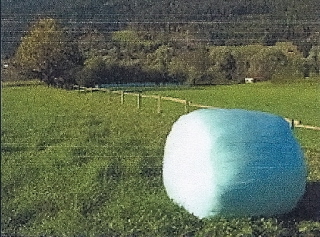

For animals that eat silage, a bale wrapper may be used to seal a round bale completely and tripper the fermentation process. it is a technique used as a money-saving process by producers who do not have access to a silo, and for producing silage that is transported to other locations. However, a silo is still a preferred method for making silage. In very damp climates, it is a legitimate alternative to drying hay completely and when processed properly, the natural fermentation process prevents mold and rot. Round bale silage is also sometimes called "haylage," is is seen more commonly in Europe than in either the USA or Australia. However, hay stored in this fashion must remain completely sealed in plastic, as any holes or tears can stop the preservation properties of fermentation and lead to spoilage.

A completely wrapped sileage bale in Austria.

Hay Conditioning

Conditioning of hay has become popular. The basic idea is that it decreases drydown time. Usually, a salt solution is sprayed over the top of the hay (generally alfalfa) that helps to dry the hay. conditioning can also refer to the rollers inside a swather that crimps the alfalfa to help squeeze out the moisture.

Safety issues

Haystacks produce internal heat due to bacterial fermentation. Hay baled from moist grass can produce enough heat to set the haystack on fire. Farmers have to be careful about moisture levels to avoid spontaneous combustion, which is a leading cause of haystack fires.

Due to its weight, hay can cause a number of injuries to humans, particularly those related to lifting and moving bales, as well as risks related to stacking and storing. Hazards include the danger of having a poorly-constructed stack collapse, causing either falls to people on the stack or injuries to people on the ground who are struck by falling bales. large round hay bales present a particular danger to those who handle them, because they can weigh over a thousand pounds and cannot be moved without special equipment. Nonetheless, because they are cylindrical in shape, and thus can roll easily, it is not uncommon for them to fall from stacks or roll off the equipment used to handle them From 1992 to 1998, 74 farm workers in the United States were killed in large round hay bale accidents, usually when bales were being moved from one location to another, such as when feeding livestock.

Hay is generally one of the safest feeds to provide to domesticated grazing herbivores. However, some precautions are needed. Amount just be monitored so that animals do not get too fat or too thin. Supplemental feed may be required for working animals with high energy requirements. Animals who eat spoiled hay may develop a variety of illnesses, from coughs related to dust and mold, to various other illnesses, the most serious of which may be botulism, which can occur if a small animal, such as a rodent or snake, is killed by the baling equipment, then rots inside the bale, causing a toxin to form. Some animals are sensitive to particular fungi or molds that may grow on living plants. For example, an endophytic fungus that sometimes grown on fescue can cause abortion in pregnant mares. Some plants themselves may also be toxic to some animals. For example, Pimelea, a native Australian plant, also known as flax weed, is highly toxic to cattle.

Article taken from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia